Aug 8th

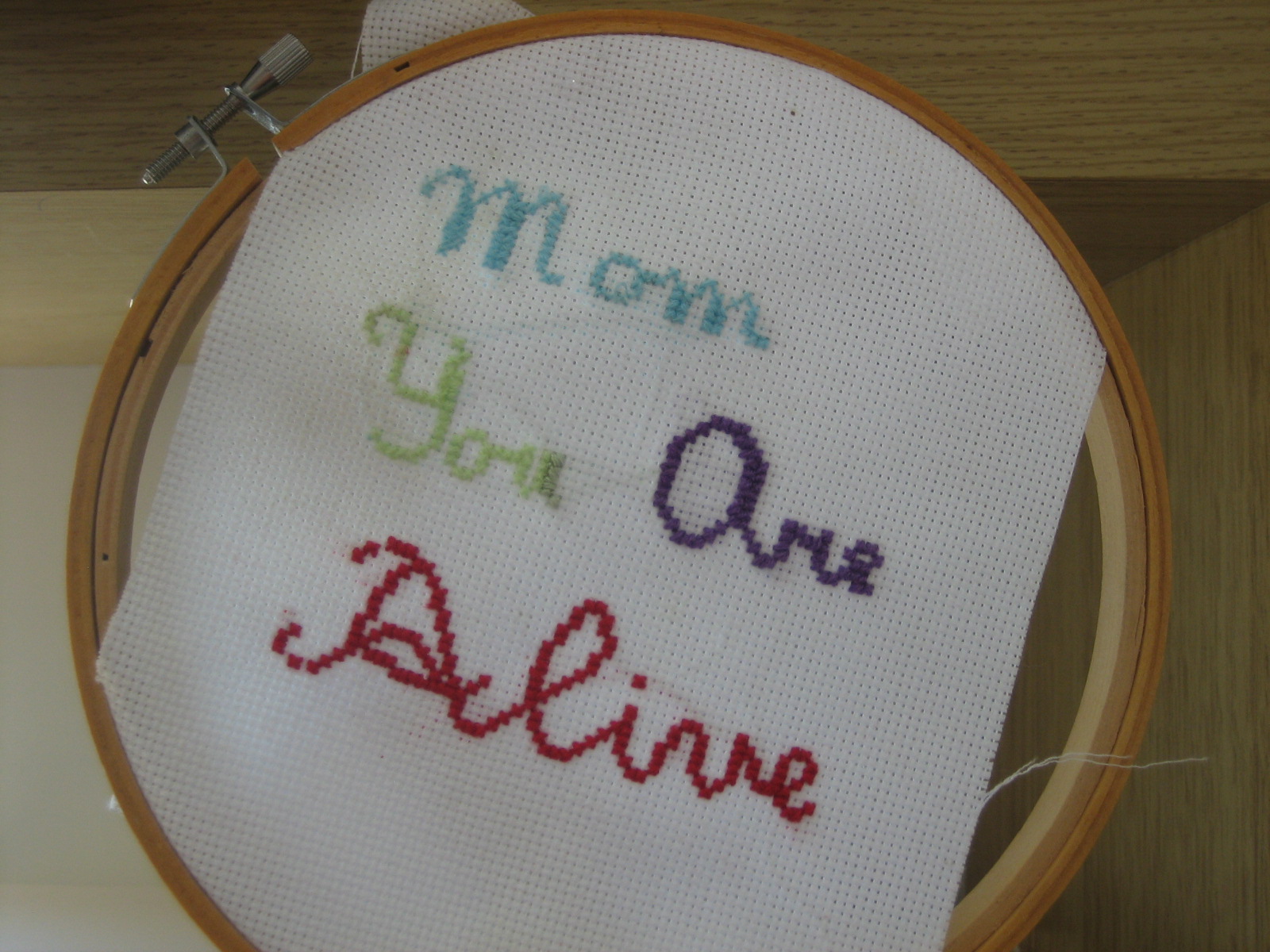

Not long ago, my mother and I found an embroidered piece of cloth I had started more than twenty years ago. It said “mom, you are”. Hiding my surprise, I realized that I had never forgotten it. In all these years I hadn’t resolved the confusion of the 8-year-old self, I had only learned to live with it.

The embroidered cloth was meant to be a present for my mother’s birthday. With all my might I wanted to say something meaningful – something that wasn’t just flattery, dishonest, or just about me. I tried on every word I knew, both in English and in Russian, but nothing fit.

My mother’s survival was the single most important thing in my life but I didn’t understand why. I didn’t aspire to be her at first, nor did I notice our similarities in character. I didn’t have any fantastic stories or memories of adventures to start this homage. In fact, so imbedded was her presence in my life when I was growing up, I almost didn’t notice her at all or she just became a part of every moment. Describing my mother with a few words was as impossible a task as describing a line by a blot of ink somewhere in the middle of it, or a novel by a single letter on one of the pages. Disappointed with myself, I resigned to not say anything at all.

With the years rolling over my memories, turning over fresh soil where old plants once grew, I’ve had long enough. More time does not mean more infinity, as Bolaño carefully reminded me. Perhaps to find the right word, I should have started backwards: “mom I am…”, which is only slightly easier in theory but I had already started in embroidery and not in theory.

My memories of who I was at eight are all of one flavor. I can say with some certainty that my childhood was marked by two occurrences: 1) I was given my mother’s name, and 2) death was my first conscious memory of life. Everything else followed.

In the hospital, I was first an Anna, but the mistake was quickly caught and I was renamed Lena. Whether this meant that I looked like my mother, I don’t know. I have never thought of myself as a Lena Jr. (or Lena II) because I have never thought of my mother as a Lena and because I hated the number two. Somehow the name doesn’t suit either of us, but it was hers to give to me, which made all of the difference.

When I was three, a red phone rang in our Moscow home. In my memory of the day, the phone had a rotary dial and a curly chord that dangled almost to the floor from its mount on our kitchen wall. This particular ring distinguished itself from its first crackle, rippling through the air like an alarm or a wake-up call. When my mother picked it up and tentatively said hello, I sensed that she already knew the news that the woman on the other end was charged with delivering. After the words were served (they must have tasted like cold liver), my mother dropped the phone and started weeping. Her father had finally died in the hospital.

The phone swung slowly from side to side as my mother wept with control but no strength. I listened to the blank dial tone and I listened to the sobs in alteration, waxing and waning in front of my nose. At times I have felt that picking up that phone and putting it back in its cradle was the only real choice I ever made. From that time on, I knew about death, I knew it had marked me. Not in the melodramatic sense that we all die – that bothered me in a different way – but that I would think about it constantly in the detached way people study neurons in a pitri dish.

For a long while after, things happened that I didn’t remember. There must have been a funeral where vague words were exchanged, a time of grief, a time for moving on, but I couldn’t recall any of it. I only remember that a year or two later, still in Moscow, I asked my mother how it could be that living things could just die and be replaced by nothing. How is it possible to exist and then to just not? What happens to all those feelings and thoughts?

It was then that my mother told me the story of Jesus. It didn’t matter that I was a natural disbeliever or that for a long time I didn’t understand what Jesus had to do with my question about nothingness. The stories were filled with some essence of what it meant to be human. I grew so fond of stories that I told them to anybody who would listen. Usually they were in the form of lies, but that didn’t matter either. The stories were alive; they were the fuel for my soon-to-be-discovered imagination.

When my memories started to visit me more often, I was 7 and we were now in a different house, a different country. My mother was moaning from her bedroom with one of her paralyzing migraines. My little brother was riding an orange skateboard on his knees into every wall in the house while my older sister sang something she had just learned in English at the top of her lungs. I was in agony trying to get the whole world to wait in silence until the headaches went away. Nothing worked, until I came up with an idea: what if I imagined that these were my headaches? Could I take up my mother’s pain, displace it? How much pain could there really be? The thoughts didn’t fix the headaches but they made me feel that my despair could protect her.

This torment became my ritual. I waited by the windowsill asking repeatedly “where’s mama, what’s taking her so long” every time she left the house, even if just to the grocery store. I would imagine her being mugged and then quickly replace her face with mine. Each time I pictured a new form of death: car accident, stroke, slipped on leaves, eaten by a mountain lion. These dramatizations, once imagined, couldn’t possibly happen in real life; how could reality be as cheap as to mimic a child’s imagination? It was as if by measuring the scenario with my thoughts I was collapsing reality’s wave function and eliminating uncertainty. I didn’t understand physics but this intuition made more sense to me than any of the grade school spelling tests I failed.

And in this fashion my childhood continued. The context evolved but the thoughts were always the same. I truly believed that I could control the unpredictability of life with my imagination. Superstitions – a close relative of the imagined – were added to the repertoire. When I took up tennis and fell in love with the sport, it quickly transformed from a game to a sequence of rituals. I forbade myself to watch TV, I imagined myself winning Wimbledon each night, I only held tennis balls in my right pocket, and I always stepped with the right foot across the baseline. All of these things had a way of protecting what I loved from fading. The problem was that the list of images and rules only kept growing and I was drained from the constant effort to remember them all.

Around that time, I started having recurrent nightmares. I had dreams that in a black abyss a thin white line slowly crawled its way from the right edge of my mind to the left. The line, innocuous enough at first, grew larger and gained speed. As it grew, its edges became unclear and frayed. It emitted a noise as it scratched through the void like fuzzy static. The line became so large, so fast, and so loud that it engulfed the black abyss completely.

I woke up from these dreams in a panic as if I had fallen inside the line as well. In my first attempt at research, I read Jung and Freud to decipher the dream’s meaning. The void was a fear of death, said the experts. But in my dreams it was the white line that terrified me. It wasn’t darkness; it was the white line that was swallowing it. I wasn’t scared of death, I was scared of life swallowing all of the dead – eating memories of everything that has ever lived like a hungry dinosaur.

Would I forget my mother too? Would I lose interest in tennis? Will the unstoppable line kill them both? By guarding my mother and everything else I loved from death, was it my own memories I was guarding from life? With my mother still here, I couldn’t possibly begin to forget her. After I woke from these dreams, I would tell her that I wanted to cut her head off when she died and keep it in a jar on the bookshelf so I could look at it every day. I thought I was paying her the highest of compliments.

The irony of it was of course that by forcing an inflexible devotion to tennis through demanding routines, I lost sight of why I loved to play. By keeping my mother locked up in this shrine where not even breath was allowed to enter, I was forgetting her all the time.

In all of these difficult memories, where was my mother really? Was she the inanimate helpless creature of my imagination, moaning and getting struck by cars? Or was she the one dancing to Abba’s Happy New Year? Wasn’t it her limbs that flapped around in dance with all the happiness and sense of the living? Wasn’t it my mother who used to race me across the fields barefoot, and win?

For my vain attempts to control it, life has gifted me a consolation prize: a better pair of glasses, but only for eyes that look into the past. I’m still the eight year old who worries and performs rituals to ward off life’s indifference to what no longer belongs to it. But I now recognize that while my morbid imagination was busy protecting, I was preventing everything I loved from just being.

If I couldn’t find the word to describe my mother, perhaps it was because I missed her real life altogether. While I was agonizing about her health, she was in Nicaragua eating and playing ball with the local orphans. While I was worrying about her broken bones, she was galloping and jumping horses. While I was fixed on closing family wounds and negotiating compromises, she was grieving with her whole heart. While I was obsessed with protecting my mother from death, she was busy being Alive.